Word of the Day

wont

adjective

accustomed; used (usually followed by an infinitive): He was wont to rise at dawn.

More about wont

The history of the adjective, noun, and verb wont is as confused as its three modern pronunciations. The Middle English adjective has many variant spellings, among them wont, woned, wonde (the root vowel is short, as in one of the modern pronunciations). Wont, woned, and wonde (and many other variants) are the past participle of the verb wonen (with many variant spellings) “to inhabit, live (somewhere); to continue to be (in a state or condition); to be accustomed.” Wonen comes from Old English (ge)wunod, past participle of (ge)wunian, (ge)wunigan “to dwell, inhabit, remain, be (in a certain condition).” Old English (ge)wunian is akin to Old High German wonēn “to dwell, remain” and German gewöhnen “to accustom.” Wont (adjective) first appeared in writing in the 9th century; the noun wont in the 14th century; and the verb wont in the first half of the 15th century.

how is wont used?

Ahab was wont to pace his quarter-deck, taking regular turns at either limit, the binnacle and mainmast ….

Young people are the primary drivers of language change, but even we “olds”—as the young are wont to put it—like to change things up now and then.

wont

More about sciolism

English sciolism “superficial knowledge, a pretension to learning,” comes from the Late Latin adjective and noun sciolus “pretending to knowledge; a person who pretends to knowledge,” and the common noun suffix -ism, originally Greek but completely naturalized in English. Sciolus comes from Latin scius “knowing, knowledgeable, cognizant,” a derivative of the verb scīre “to know (a fact), know for sure.” The obsolete English noun sciolus “one who possesses only superficial knowledge, particularly and especially an editor of a text,” comes directly from Late Latin sciolus. The uncommon English noun sciolist “a person of superficial knowledge or learning” is another derivative of sciolus. Sciolism entered English in the mid-18th century.

how is sciolism used?

Anderson faded, his showy sciolism proving as tiresome to voters as it had to his congressional colleagues.

An unseemly air of sciolism creeps into our insistence that we others know the difference between Benedict Arnold and Arnold Bennett.

sciolism

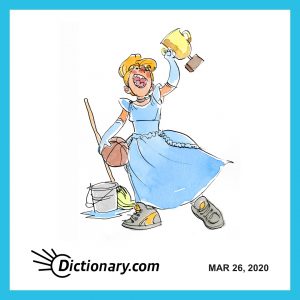

Cinderella

noun

a person or thing that achieves unexpected or sudden success or recognition, especially after obscurity, neglect, or misery.

More about Cinderella

Cinderella is a partial translation of French Cendrillon “Little ashes,” from Charles Perrault’s Cendrillon ou la petite pantoufle de verre “Cinderella or the Little Glass slipper” (1697). The story of Cinderella is ancient: The Greek geographer and historian Strabo tells the earliest recorded version of the folk tale in his Rhodopis (written between 7 b.c. and a.d. 24), the name of a Greek slave girl who married the King of Egypt. The first modern European version of the folk tale appears in Lo cunto de li cunti “The Tale of Tales” (also known as the Pentamerone), the collection of fairy tales written in Neapolitan dialect by the Neapolitan poet and fairy tale collector Giambattista Basile (1566-1632), from whom Charles Perrault and the German folklorists and philologists the Brothers Grimm later adapted material. Cinderella entered English in the 19th century.

how is Cinderella used?

The first Cinderella in the era of the 64-team bracket may be the greatest in history.

Ukraine is the new Cinderella. It could just metamorphose from bankruptcy and potential civil war to surpass elder sister Russia in reform and perhaps even consensus.

Cinderella