Word of the Day

rhathymia

noun

carefree behavior; light-heartedness.

More about rhathymia

Rhathymia “carefree behavior, lightheartedness” comes straight from Greek rhāthȳmía (also rhāithȳmía, rhāḯthȳmía) “easiness of temper, taking things easy.” Rhāthȳmía is a derivative of the adjective rhā́ithȳmos “easygoing, good-tempered,” but also “frivolous; indifferent, slack.” The first part of rhāthȳmía is the adverb rhã, rhéa, rheīa “easily, lightly” (its further etymology is unknown). The second element of rhāthȳmía is a derivative of the noun thȳmós “soul, spirit, mind, life, breath.” The combining form of thȳmós, –thȳmía, is used in English in the formation of compound nouns denoting mental disorders, such as dysthymia, alexithymia, and cyclothymia. Rhathymia entered English in the first half of the 20th century.

how is rhathymia used?

Rhathymia is the preferred mode of presentation of the self.

From this sprang slackness, rhathymia, long delays in reaching decisions or paying out salaries, and downright callousness in ignoring positive distress.

rhathymia

ductile

adjective

capable of being molded or shaped; plastic.

More about ductile

The adjective ductile, “capable of being molded or shaped; plastic,” comes from Middle English ductil, “beaten out or shaped with a hammer,” from Old French ductile or Latin ductilis, “capable of being led along a course; malleable, ductile.” Ductilis is a derivative of duct-, the past participle stem of the verb dūcere “to draw along with, conduct, lead,” one of the verb’s dozens of meanings being the relatively rare “to model or mold material; draw out (metal) into wire.” In modern technical usage, ductile is restricted to “capable of being drawn out into wire or threads,” a quality of the noble metals such as silver and gold; malleable in technical usage covers the sense “capable of being hammered or rolled out into thin sheets,” another quality of the noble metals. Ductile entered English in the 14th century.

how is ductile used?

Ductile and sensuous, paint hugs the flat photographic forms of Leiter’s nudes in a tailor-made mantle.

she cheerfully proposed reading; complied with the first request that was made her to play upon the piano-forte and the harp; and even, to sing; though, not so promptly; for her voice and sensibility were less ductile than her manners.

ductile

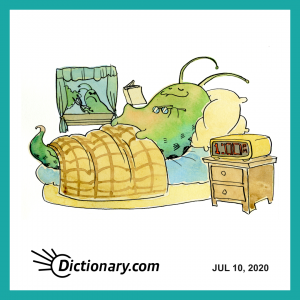

slugabed

noun

a person who lazily stays in bed long after the usual time for arising.

More about slugabed

Slugabed is a relatively uncommon noun meaning “a person who lazily stays in bed long after the usual time for arising.” The noun slug, “a snaillike animal; a lazy person, sluggard,” developed from Middle English slugge “a lazy person; slothfulness, the sin of sloth.” Slugge probably comes from Old Icelandic slōkr “clumsy person,” Swedish and Norwegian dialect slok “lazy person,” Danish slog “rascal, rogue.” The element –a– is simply a reduced form of the Old English preposition on “on, in, into”; bed comes from Old English bedd, ultimately from the Proto-Indo-European root bhedh-, bhodh– “to dig, bury,” from which Latin derives fodere “to dig” and fossa “a ditch, trench, groove”; the Celtic languages have Welsh bedd, Cornish bedh, and Breton béz, all three meaning “a grave.” Slugabed entered English in the late 16th century.

how is slugabed used?

“Auntie…” he said. “Don’t you Auntie me, you slugabed! There’s toads to be buried and stoops to be washed. Why are you never around when it’s time for chores?”

‘I am not a slug-a-bed, Harriet.’ Asobel’s voice was high and clear across the garden, ‘I get up as soon as my eyes pop open.’

slugabed