Word of the Day

bight

noun

a bend or curve in the shore of a sea or river.

More about bight

Bight has several senses in Modern English. It can refer to a bend or curve in the shore of a sea or river, a body of water bounded by such a bend, or the loop or bent part of a rope. Following the twists and turns of its morphology, we arrive at Middle English byght, bight, beghte, beythe “the fork of the legs, the pit or hollow of the arm, (in names) bend or bay,” from Old English byht “a bending, corner, dwelling, bay, bight.” The English word comes from Germanic buhtiz, from the Proto-Indo-European root bheug(h)-, bhoug(h)-, bhug(h)– “to bend,” which is the source of Sanskrit bhujáti “(he) bends,” Gothic biugan and Old English būgan, both meaning “to bow,” and Old English boga “arch, bow” (as in English rainbow and bow and arrow).

how is bight used?

The boardwalk weaves along the bight from the ferry terminal on Grinnell to the end of Front Street.

A bight is simply a long and gradual coastal curve that creates a large bay, often with shallow waters. You’re likely already familiar with a number of bights — for instance, the area between Long Island and New Jersey on the East Coast is known as the New York Bight, while California’s Channel Islands live in the Southern California Bight, which stretches all the way from Santa Barbara to San Diego.

bight

lugubrious

adjective

mournful, dismal, or gloomy, especially in an affected, exaggerated, or unrelieved manner: lugubrious songs of lost love.

More about lugubrious

The source of English lugubrious is the Latin adjective lūgubris “mournful, sorrowful,” a derivative of the verb lūgēre “to mourn, grieve.” The meaning of lūgēre is closely akin to the Greek adjective lygrós “sad, sorrowful,” and both the Latin and the Greek words derive from the Proto-Indo-European root leug-, loug-, lug– “to break,” source of Sanskrit rugná– (from lugná-) “shattered” and rujáti “(he) breaks to pieces, shatters,” Old Irish lucht and Welsh llwyth, both meaning “load, burden,” Lithuanian lū́žti “to break” (intransitive), and Old English tō-lūcan “to tear to pieces, tear asunder.” Lugubrious entered English in the early 17th century.

how is lugubrious used?

The radio slid from mournful to downright lugubrious. Ridiculously lugubrious. There was even sobbing in the background. Talk about melodramatic.

Cohen’s lugubrious tones always divided opinion; for some they were intrinsic to his melancholic charms, to others a turn-off that blindsided them to the genius of his songcraft, which was always gilded, its cadences measured, its images polished.

lugubrious

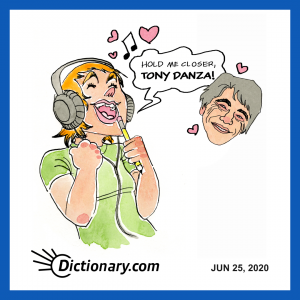

mondegreen

noun

a word or phrase resulting from a mishearing of another word or phrase, especially in a song or poem.

More about mondegreen

The trouble with mondegreens is that they are usually so hysterically funny that you cannot stop citing examples of them instead of describing their “taxonomy” and history. Mondegreen was coined by the U.S. writer and humorist Sylvia Wright (1917-81), who wrote in an article in Harper’s Magazine: “When I was a child, my mother used to read aloud to me from Percy’s Reliques, and one of my favorite poems began, as I remember: ‘Ye Highlands and ye Lowlands, / Oh, where hae ye been? / They hae slain the Earl Amurray, / And Lady Mondegreen,’” the last line being a child’s mishearing and consequent misunderstanding of “laid him on the green.” Ms. Wright persisted in her idiosyncratic version because the real words were less romantic than her own (mis)interpretation in which she always imagined the Bonnie Earl o’ Moray dying beside his faithful lover Lady Mondegreen.

how is mondegreen used?

We’ve been misunderstanding song lyrics for decades, Elton John’s “hold me closer, Tony Danza”—er, “tiny dancer”—included. These funky musical mishearings even have their own name: mondegreens.

We still have mondegreen moments. Even though I know Creedence Clearwater Revival is singing, “There’s a bad moon on the rise,” lately it sounds suspiciously like “There’s a bathroom on the right.”

mondegreen