Word of the Day

adamantine

adjective

utterly unyielding or firm in attitude or opinion.

More about adamantine

Adamantine “unyielding in attitude or opinion; too hard to cut, break, or pierce; like a diamond (in luster)” comes from Middle English adama(u)ntin, from the Middle French adjective adamantin (feminine adamantine), from Latin adamantinus “pertaining to diamondlike adamant or steel; resembling diamonds (saxa adamantina), from Greek adamántinos, an adjective derived from the noun adámas (stem adamant-) “steel (the hardest metal); diamond.” The traditional etymology for adámas is the corresponding adjective meaning “unbreakable,” somehow a derivative of damân “to tame, subdue,” with the privative prefix a-; more likely adámas is a loanword from Semitic. Adamantine entered English in the first half of the 13th century.

how is adamantine used?

Her dedication to the pursuit of equality for the masses was adamantine, however.

And the moment of commitment came with the special force that was central to his character: an adamantine, unshakable conviction that what he was doing was unequivocally right …

adamantine

sojourn

noun

a temporary stay: during his sojourn in Paris.

More about sojourn

The noun sojourn means “a temporary stay.” The verb sojourn, “to stay for a time, reside temporarily,” has several dozen Middle English spellings: sojournen, sojourni, suggorn, suggeourn, etc. The Middle English forms derive from equally exuberant Old French forms, for example, sejorner, sojorner, sojourneir, sojurner, and Anglo-French forms, for example, sojurner, sujurner. The French forms derive from an unrecorded Vulgar Latin verb subdiurnāre “to stay for a time,” a compound of the preposition and prefix sub, sub-, here meaning “a little, for a while” and the Latin verb diurnāre “to live for a long time,” a derivative of the Latin adjective diurnus “belonging to the daytime, occurring every day.” Sojourn entered English in the 13th century.

how is sojourn used?

Nevertheless, in this mansion of gloom I now proposed to myself a sojourn of some weeks.

He begins to conjecture how much he has gained and lost during his long sojourn in the American republic.

sojourn

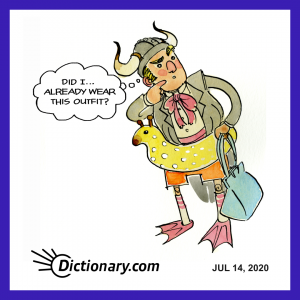

déjà vu

noun

the illusion of having previously experienced something actually being encountered for the first time.

More about déjà vu

The late, great social philosopher Lawrence “Yogi” Berra is credited with saying “It’s déjà vu all over again,” referring to Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris constantly hitting back-to-back home runs for the Yankees in the early ’60s. This “Yogi-ism” aside, déjà vu, literally “already seen,” is the illusion of having previously experienced something actually being encountered for the first time, a term used in psychology. The phrase is French; it was first used and perhaps coined by Emile Boirac (1851–1917), a French philosopher and parapsychologist. Déjà “already” comes from Old French des ja “from now on”; des comes from Vulgar Latin dex or de ex, a combination of Latin prepositions dē “of, from” and ex “out, out of.” Ja “now, already,” comes from the Latin adverb jam with the same meaning. Vu comes from Vulgar Latin vidūtus or vedūtus, equivalent to Latin vīsus, past participle of vidēre “to see.” Déjà vu entered English in the early 20th century.

how is déjà vu used?

Trapped in a time loop: That’s how one man felt because of his recurring episodes of deja vu.

A person experiencing déjà vu is no more likely to accurately predict what they’re going to see around the next corner than someone who is blindly guessing.

déjà vu