To modern ears, the following excerpt from Anthony Trollope’s He Knew He Was Right, published in 1869, sounds risqué. Trollope writes:

It is not pleasant to make love in the presence of a third person, even when that love is all fair and above board; but it is quite impracticable to do so to a married lady, when that married lady’s sister is present.

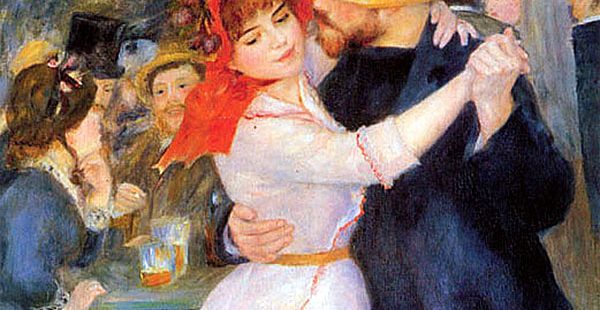

As shocking as those sentences might sound to us, readers in Victorian times would have thought nothing of it. No, this scene does not refer to a sexually voyeuristic experience for the “third person.” Rather Trollope writes of chaste courtship, the variety traditionally exercised in sophisticated 19th-century society, often with a chaperone present.

As Fraser Sutherland notes in his essay “Why Making Love Isn’t What It Used to Be,” the term make love has undergone a semantic shift over the last several centuries: “In English the phrase early on both referred to wooing and to sexual intercourse…Yet euphemistic usage was firmly entrenched by the early seventeenth century, and remained so into the early twentieth century.” In Victorian times, the popularity of the euphemistic sense reflects the cultural niceties of a characteristically subdued society. It wasn’t until the 1920s that make love reverted back to its physical sense, which had receded into the fringes of the English language. During an era of female empowerment marked by the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment, make love regained its somewhat forgotten carnal connotations, starting in the United States. This semantic change is not an isolated incident. Sutherland also notes that the term lover experienced a similar shift in these same periods.

By the time the phrase “make love, not war” arose as a 1960s anti-war slogan, the Victorian parlor-room-appropriate courtship connotations of make love had long since morphed into something more sexually explicit. Of course in this context, make love also stands in for peace and compassion. For younger generations make love is a loaded expression. While some use it sincerely, others find the use of make love to be sickly saccharine and roll their eyes at its overly sentimental quality.

Next time you pick up a Victorian novel involving courtship, keep in mind the evolution of the phrase make love over time. Though these books might be more tame than some readers might have previously thought, there’s still plenty of scandal, intrigue, and passion within their pages.