by Rory Gory

No matter your sexual orientation or gender identity, all people have something in common. There are many things in life that we can choose or change, such as how we decide to express ourselves, the relationships we commit to, or the dreams we pursue.

And then there are things in life that happen to us whether or not we want them to: our genetic makeup, the environment we are raised in, and the opportunities that are available to us, as a few examples. The constant challenge is taking responsibility for what we can influence—and acknowledging what we cannot.

But for LGBTQ people, words like choice and change—which seemingly imply power and possibility—have actually been weaponized throughout a painful history of criminalization, abuse, and harm inflicted on people for simply being who they are.

Mental Illness Awareness Week starts on October 4, culminating with World Mental Health Day on October 10. During this time, it’s critical to destigmatize conversations around mental health. It’s also an ideal time to raise awareness for how LGBTQ youth are at a higher risk for poor mental health outcomes and suicidality—not because of something intrinsic to being LGBTQ, but rather because of the increased experiences of victimization and discrimination as well as traumatic practices they may be subjected to, including conversion therapy.

Just as it’s important to learn why words like commit shouldn’t be used in conversations around suicide, learning how words such as choice, change, and convert can be used to harm LGBTQ people is important to being an advocate for mental health and an ally to LGBTQ people.

Can you choose or change your identity?

A choice is defined as “the right, power, or opportunity to choose.” Humans dislike the idea that there are things about ourselves that we don’t have the power to choose. It is that age-old tension between fate and free will, between what life gives us and what we do with it. While we can choose how we respond, we ultimately don’t have much power over how we innately feel. Sexual orientation and gender identity are not a choice, but whether we accept or like our identity is a different issue.

There are some things about ourselves we can change, that is, “to transform or convert.” You can change how you express your gender, such as choosing to wear something traditionally coded as masculine, like a tuxedo, or choosing to wear something traditionally coded as feminine, such as a dress. Whether you wear a tux or a dress may influence how people interpret your gender (and it may bring joy or embarrassment), but clothing alone cannot change your inner sense of gender identity or who you’re attracted to.

So the answer is simple: No, you cannot choose your sexual and romantic orientation or your gender identity and it is also not able to be changed. LGBTQ people exist whether they are allowed to live authentically or not.

But you generally can choose whether to take a particular action, right? Of course. You can be attracted to someone, but never ask them out, for instance. And there are times when people make choices such as abstaining from sex before marriage, or commitments that require celibacy, like certain priesthoods. The key difference is that a choice to be abstinent or celibate is not the same thing as fundamentally changing one’s identity. A person who chooses to be celibate is not, therefore, asexual. A person who chooses not to come out or disclose their identity is not straight or cisgender by default.

If a major life choice is based in healthy beliefs and an alignment with one’s sense of self, inner purpose, and identity, it can be a good choice. However, if a choice is based in fear, condemnation, conditional love, or control, it is more likely to have negative consequences for one’s mental health.

There are some gender identities that are fluid, for example, people who identify as genderfluid or genderflux may experience their gender as fluctuating between a variety of identities and expressions. Many sexually fluid people exist as well, and some may identify as bisexual or pansexual; others choose not to label their sexualities. But again, that experience is not a choice, it is innate: If your sexuality or gender identity is fluid, it remains fluid no matter how you express your gender or who you’re currently partnered with. While one may experience fluctuations in one’s gender identity or sexuality over time, it’s not possible to forcibly change a person’s orientation or identity, even if they have a fluid gender or sexuality. Nor is it possible to cause a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity to become fluid if it is not.

Sexuality and gender are not mental illnesses

And how we define terms related to them should not suggest they are.

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) determined that homosexuality was not a mental illness in 1973. Homosexuality is used pointedly here. Dictionary.com, in line with recommendations from GLAAD and the APA, has replaced references to homosexual with gay, gay man, or gay woman. It also has replaced references to homosexuality with gay or lesbian sexual orientation.

Gay vs. homosexual: Why there’s a difference

The previously used, outmoded terms, homosexual and homosexuality, originated as clinical language, and dictionaries have historically perceived such language as scientific and unbiased.

But homosexual and homosexuality are now associated with pathology, mental illness, and criminality, and so imply that being gay—a normal way of being—is sick, diseased, or wrong. While these terms may still be used in certain contexts (for example, in legal decisions interpreting nondiscrimination laws where “homosexuality” appears), today homosexual is most frequently used by those who wish to signal opposition to LGBTQ equality and is considered by many to be a pejorative.

Find out other major changes Dictionary.com made to reflect and respect the LGBTQ community and experience in its article, “Dictionary.com Releases Its Biggest Update Ever.”

But while the APA ended the pathologizing of being gay in 1973, the practice of conversion therapy has continued. And for transgender and nonbinary people, the fight to be treated fairly by medical providers continues to this day.

It’s important to note that while gender dysphoria (which some, but not all, transgender and nonbinary people experience) can cause mental distress, the APA has clarified that being transgender is not a mental illness. The World Health Organization also no longer categorizes being transgender as a mental disorder after a major resolution to amend its health guidelines was approved in 2019.

So-called “therapies” that promise to change or convert a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity are widely discredited. Conversion therapy is widely opposed by prominent professional medical associations including the American Psychological Association, American Psychiatric Association, the American School Counselor Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Medication Association.

While conversion therapy in no way succeeds in changing a person’s identity, it can have a devastating effect on the subject’s mental health. According to The Trevor Project’s peer-reviewed article in the American Journal of Public Health, LGBTQ youth who underwent conversion therapy were more than twice as likely to report having attempted suicide and more than 2.5 times as likely to report multiple suicide attempts in the past year compared to those who did not.

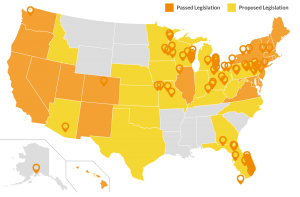

Is conversion therapy still happening?

Tragically, yes. To this day, so-called conversion therapy or reparative therapy is still widespread across the US and around the world. Words like convert, repair, and therapy are used to hide the harmful impact of a fraudulent practice that doesn’t change a person’s identity but does contribute to significantly higher rates of suicidality.

One of the main barriers The Trevor Project has uncovered while advocating to protect LGBTQ youth from this practice across the country is that many people are convinced that conversion therapy is a thing of the past. Movies such as Boy Erased (2018) and The Miseducation of Cameron Post (2018) have helped to educate audiences about the abuses that happen at conversion therapy centers, but still, many people are unaware that conversion therapy is happening legally in their states.

*Click the map above for a larger view.

According to studies by the UCLA Williams Institute, more than 700,000 LGBTQ people have been subjected to conversion therapy, and many more LGBTQ youth will continue to experience this unprofessional conduct this year, often at the insistence of well-intentioned but misinformed parents or caretakers.

You can take action with The Trevor Project to help end conversion therapy in the United States. If conversion therapy is still legal in your state, you can help even beyond statewide legislation by working on a municipal level to pass legislation and raise public awareness for this issue.

So how do these words harm LGBTQ people?

Even though sexuality and gender are not mental illnesses, this hasn’t stopped many from claiming that they can convert people to heterosexual or cisgender identities, such as with conversion therapy, or repair their sexuality or gender identity with reparative therapy. As awareness has been raised for the harms associated with conversion therapy, the same discredited practice has once again rebranded, this time using the language of gender-critical therapy or “therapeutic choice” for “unwanted homosexual attractions,” among other terms.

Whether one is criticizing, judging, attempting to cure, or trying to repair a person’s gender or sexuality, the result is harm: these actions tell LGBTQ people that their authentic selves are wrong, bad. That they are some problem to be addressed.

But attempts to hide, paper over, or reinvent the language of conversion and reparative therapy persist. For example, while the American Academy of Pediatrics does not condone conversion therapy, the misleadingly named American College of Pediatricians (ACPeds), a designated hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center, supports “gender criticism.”

While the phrase evokes a gender studies class in college, the term is being manipulated to communicate and advocate for conversion therapy and anti-transgender laws or policies. It’s very important to do one’s due diligence when looking for trans-affirming healthcare, and stay alert for well-worded misinformation and disinformation that perpetuates scientifically inaccurate theories about LGBTQ people.

The GLAAD Media Reference Guide also outlines words that may be used to discredit, invalidate, or stigmatize LGBTQ people. For example, the term “transgenderism” is not a word, but GLAAD defines it as, “a term used by anti-transgender activists to dehumanize transgender people and reduce who they are to “a condition” or ideology.

Other examples of defamatory language used for trans and nonbinary people can include words like deceptive, counterfeit, or describing a person as posing as a particular gender, as it implies that a person’s gender is a lie. An agenda is defined as “a list, plan, outline, or the like, of things to be done, matters to be acted or voted upon, etc.,” and that definition alone makes phrases like gay agenda or homosexual agenda harmful. LGBTQ people don’t have a plan to carry out, yet these phrases, which are also inventions of anti-LGBTQ extremists, make it seem like there is an ulterior motive. Disparaging language for queer people also include, more insidiously, phrases like sexual preference or lifestyle, which both suggest that one’s identity is merely some casual choice and invoke various harmful stereotypes.

How language can affirm LGBTQ people

While anti-LGBTQ extremists, and well-intended but uninformed people, may use invalidating language, there are many ways to embrace language to affirm and support LGBTQ people. We can start by honoring the new words LGBTQ youth are using to describe themselves.

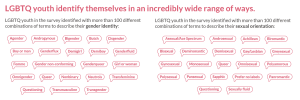

LGBTQ youth surveyed in The Trevor Project’s 2020 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health identified with more than 100 different combinations of terms to describe their gender identity and sexual orientation! One in four LGBTQ youth surveyed reported using pronouns or pronoun combinations that fall outside of the binary construction of gender. Beyond just settling with a single label to encompass the nuances of attraction and identity, LGBTQ youth are exploring a variety of words to accurately communicate their sexual and romantic orientations, relationship types, and gender identity.

The Trevor Project. (2020). National Survey on LGBTQ Mental Health. New York, New York: The Trevor Project.

*Click the map above for a larger view.

To make it easier, The Trevor Project and Dictionary.com have partnered on numerous articles on the evolving language that LGBTQ youth are using. You can learn about the difference between sexual and romantic orientations, including asexual identities, and take a deeper dive into words for bisexual, pansexual, and other multisexual identities. Gain a deeper understanding of words for gender identity, including nonbinary and genderfluid identities, and learn how the letter X has influenced new gender-neutral terms.

While all these new words may seem intimidating, you don’t have to learn every single one to be a good ally. Start by listening to others and using the words that they themselves use to describe their identity. This also entails respecting a person’s name and pronouns. Pronouns like the gender-neutral singular they, or other pronouns such as ze, xe, or ve can be used in addition to the more commonly known she and he.

This is also key: It’s outdated to ask for someone’s preferred pronouns.

Instead, simply ask for their pronouns. Many LGBTQ people pushed back on the preferred phrasing because it implies that pronouns were just a preference and that respecting them is optional. It is more respectful for people to just introduce themselves with their pronouns and ask others to share their own.

It’s important to note that while one can choose to label one’s identity in a particular way—or choose not to label their identity—the choice of how to communicate one’s gender or sexuality is not the same as choosing one’s innate sexual orientation or gender. LGBTQ youth are using more words than ever before to describe themselves, and it’s normal to explore different terms before finding the ones that best convey who you’re to other people. It’s also normal to spend time reflecting on one’s identity and expressing it in different ways along the journey of self-understanding. We should all encourage others in their self-expression, rather than telling them which words or labels to use.

Using words to save lives

The way we communicate about and to LGBTQ young people can have a huge impact on their mental health outcomes. According to The Trevor Project’s 2020 National Survey, transgender and nonbinary youth who reported having their pronouns respected by all or most of the people in their lives attempted suicide at half the rate of those who did not have their pronouns respected.

Using language and honoring a person’s identity isn’t just nice. It can literally be lifesaving.

No one chooses their sexual or gender identity. But we all have the clear, simple choice to affirm LGBTQ people and confront words like choice, lifestyle, preference, convert, and repair when it comes to misguided or malicious efforts to change who they simply are. And advocate to protect LGBTQ youth across the country from the still-present danger of conversion therapy.

Words matter. By using words that affirm and support others, we can make the world a safer place for all LGBTQ youth.

Rory Gory is the Digital Marketing Manager for The Trevor Project, the world’s largest suicide prevention and crisis intervention organization for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer & questioning (LGBTQ) young people. If you or anyone you know is in crisis, reach out to The Trevor Project for support at: thetrevorproject.org/help.