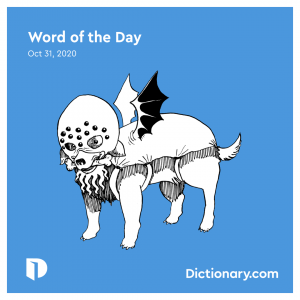

Word of the Day

leviathan

noun

anything of immense size and power.

More about leviathan

“Canst thou draw out leviathan with an hook? or his tongue with a cord which thou lettest down? Canst thou put an hook into his nose? or bore his jaw through with a thorn?” asks God of Job (Job 41). Leviathan first appears in Middle English in John Wycliffe’s translation of the Bible (ca. 1382). Leviathan comes from the Vulgate (the Latin version of the Bible, prepared by Saint Jerome at the end of the 4th century a.d.), from Hebrew liwyāthān, a kind of serpent or sea serpent or dragon of enormous size, possibly derived from the Semitic root lwy “to twist, encircle” (its etymology is uncertain). The most famous application of Leviathan is Thomas Hobbes’ book on politics, Leviathan (1651): Hobbes applied Leviathan to the state, omnipotent, totalitarian, and characterized by vast coercive machinery.

how is leviathan used?

It’s ironic that Microsoft has come to be viewed as an underdog rather than a leviathan. But recent opinion suggests that that is the case …

While much of North America has been sweltering through a summer of record heat, a group of Canadian scientists have been rafting across the Arctic Ocean on a leviathan of floating ice.

leviathan

agonist

noun

a person who is torn by inner conflict.

More about agonist

The English noun agonist comes from the rare Late Latin noun agōnista, “an athlete or combatant for a prize in the games,” a word used once by St. Augustine in a sermon. Latin agōnista betrays its Greek origin with its –ista agent suffix (borrowed from Greek -istḗs). In Greek, agōnistḗs means “a combatant, contestant (in athletic games), a champion, a pleader or public speaker,” which covers a lot of territory when you consider the roles that competitive athletic games and public speaking (including criminal and civil trials) occupied in ancient Greek life. Agōnistḗs is a derivative of the noun agōnía, one of whose many meanings is “mental or spiritual anguish, agony,” which influenced one of the English meanings of agonist but doesn’t occur in Greek agōnistḗs. Agonist entered English in the first half of the 17th century.

how is agonist used?

There was a fissure in him from the start; the dream and the business did not march together; his will was not always the servant of his intelligence; he was an agonist, a self- tormentor, who ran to meet suffering halfway.

He was an agonist. He would argue one way; he would argue another; he just didn’t want to see bigotry thrive or watch a man die.

agonist

More about eldritch

If the word is weird, eerie, and uncanny, it’s likely to be Scots, and eldritch is all of them. Most etymologists see a connection between eldritch and elf, as the early spelling variant elphrish suggests. The second syllable is likely to be Middle English riche “kingdom, realm” (from Old English rīce); the d is an excrescent or intrusive consonant between the l and the r, like chimbley for chimney in Oliver Twist: “they damped the straw afore they lit it in the chimbley.” This “Elf Kingdom” used to be exclusively Scots; the first “non-Scots” author to use the word was Nathaniel Hawthorne in his Scarlet Letter (1850). Eldritch entered English in the early 16th century.

how is eldritch used?

In this anthology podcast, the mountains of central Appalachia are haunted by the sort of sanity-draining eldritch monsters found in a Stephen King novel, or in HBO’s “Lovecraft Country.”

Despite the eldritch horrors of Toni’s princess cake, her competitors’ renditions were, somehow, even more atrocious.

eldritch