Word of the Day

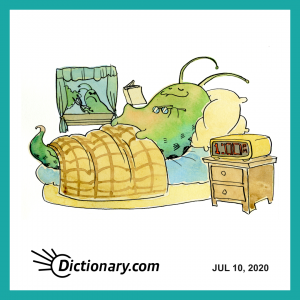

slugabed

noun

a person who lazily stays in bed long after the usual time for arising.

More about slugabed

Slugabed is a relatively uncommon noun meaning “a person who lazily stays in bed long after the usual time for arising.” The noun slug, “a snaillike animal; a lazy person, sluggard,” developed from Middle English slugge “a lazy person; slothfulness, the sin of sloth.” Slugge probably comes from Old Icelandic slōkr “clumsy person,” Swedish and Norwegian dialect slok “lazy person,” Danish slog “rascal, rogue.” The element –a– is simply a reduced form of the Old English preposition on “on, in, into”; bed comes from Old English bedd, ultimately from the Proto-Indo-European root bhedh-, bhodh– “to dig, bury,” from which Latin derives fodere “to dig” and fossa “a ditch, trench, groove”; the Celtic languages have Welsh bedd, Cornish bedh, and Breton béz, all three meaning “a grave.” Slugabed entered English in the late 16th century.

how is slugabed used?

“Auntie…” he said. “Don’t you Auntie me, you slugabed! There’s toads to be buried and stoops to be washed. Why are you never around when it’s time for chores?”

‘I am not a slug-a-bed, Harriet.’ Asobel’s voice was high and clear across the garden, ‘I get up as soon as my eyes pop open.’

slugabed

discomfiture

noun

the state of being disconcerted; confusion; embarrassment.

More about discomfiture

Discomfiture comes from Middle English desconfiture, discomfitoure, discomfiture (and many other spelling variants) “the fact of being defeated in battle; the act of defeating in battle.” One of the first occurrences of the word is in Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales (after 1387). The Middle English word comes from Old French desconfiture “a defeat, a rout.” The English sense “frustration of hopes or plans,” weakened to “confusion” or “embarrassment,” occurs at the beginning of the 15th century.

how is discomfiture used?

She had her cry out, a good, long cry; and when much weeping had dulled the edge of her discomfiture she began to reflect that all was not yet lost.

A former critical-care nurse as well as an academic philosopher, Froderberg has carefully contemplated body, soul and their fragile nexus. That pays off superbly as the air thins, and the surrealism of the terrain, the hallucinatory wanderings of oxygen-robbed brains and the discomfiture of sapped bodies converge cinematically.

discomfiture

kaput

adjective

ruined; done for; demolished.

More about kaput

The adjective kaput “ruined, done for; out of order,” is used only in predicate position, not in attributive position; that is, you can only say “My car is kaput,” but not “I’ve got a kaput car.” Kaput comes from the German colloquial adjective kaputt “broken, done for, out of order, (of food) spoiled,” which was taken from the German idiom capot machen, a partial translation of the French idioms faire capot and être capot, “to win (or lose) all the tricks (in the card game piquet).” Faire capot literally means “to make a bonnet or hood,” and its usage in piquet may be from an image of throwing a hood over, or hoodwinking one’s opponent. Unsurprisingly, kaput became widely used in English early in World War I.

how is kaput used?

“Is it as bad as that?” He shook his head. “It’s worse. If we get caught, all this is kaput. Kaput, you hear? Gone. Lost. Forever.”

The business of a woman I know has gone kaput and 15 employees are facing the sack.

kaput