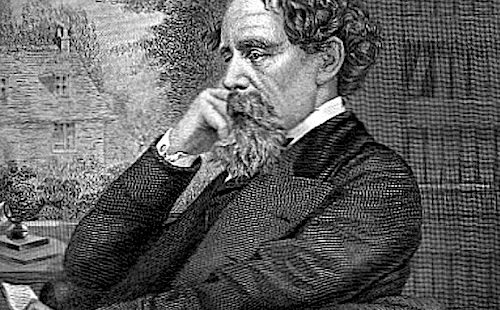

Charles Dickens is often given credit for inventing words that he was not the first to use. This is not surprising, if only because he was much more widely read than some of the people who had used these words before him. Dickens was also far more attuned to the language of the streets than were most of his contemporaries, and so his writing contains many examples of recently-invented terms. Writing in the Quarterly Review in 1839, Richard Ford refers to Dickens as the “regius professor of slang.”

In addition to the slang terms that Dickens was an early adopter of, there are a good number of standard words that he is supposed to have pulled out of his head and been the first to put on paper. Boredom is one such word.

While many people maintain that Charles Dickens invented the term boredom, this is not the case. Boredom can be found as far back as 1829, when it appears in the August 8th issue of The Albion: “Neither will I follow another precedental mode of boredom, and indulge in a laudatory apostrophe to the destinies which presided over my fashioning.” The word is in occasional use for the next couple of decades before it appears in Dickens’s Bleak House in 1853.The Pickwick Papers contained a handful of terms that Dickens popularized through his early adoption, but did not coin. Despite popular belief, Dickens was not the first writer to use butter-fingers; it makes an appearance a year before he used it, in an 1835 issue of Waldie’s Select Circulating Library. Dickens was not the inventor of the phrase devil-may-care, which also can be found the year before he used it in the newspaper The Commercial Advertiser, in 1836. Nor was he the first writer to use flummox, no matter what the wise men of the Internet may tell you; that word had been in use since at least 1832, five years before Dickens employed it in The Pickwick Papers.

There are still a large number of words for which Dickens provides us with the earliest known evidence: sawbones seems likely to have its first use in his writing, as do a number of lesser-known words, such as metropolitaneously, which means “in a metropolitan manner.” And even if he did not invent some of these other words, the fact that he used them so soon after they had been first used by someone else indicates that he was well-attuned to the changing nature of the English language. Dickens may have been inventive, and he may have been a prodigious user of new words, but he did not invent boredom, and we should stop saying that he did.

But those of you who are not fans of nineteenth-century serialized literature, and who have had the pleasure of wading through all 952 pages of Nicholas Nickelby may take a different tack: you can now say “Charles Dickens may not have invented boredom, but he certainly perfected it.” This is not a statement with which I am not prepared to argue.