Word of the Day

More about eldritch

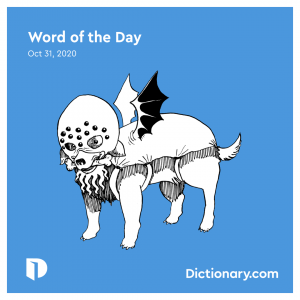

If the word is weird, eerie, and uncanny, it’s likely to be Scots, and eldritch is all of them. Most etymologists see a connection between eldritch and elf, as the early spelling variant elphrish suggests. The second syllable is likely to be Middle English riche “kingdom, realm” (from Old English rīce); the d is an excrescent or intrusive consonant between the l and the r, like chimbley for chimney in Oliver Twist: “they damped the straw afore they lit it in the chimbley.” This “Elf Kingdom” used to be exclusively Scots; the first “non-Scots” author to use the word was Nathaniel Hawthorne in his Scarlet Letter (1850). Eldritch entered English in the early 16th century.

how is eldritch used?

In this anthology podcast, the mountains of central Appalachia are haunted by the sort of sanity-draining eldritch monsters found in a Stephen King novel, or in HBO’s “Lovecraft Country.”

Despite the eldritch horrors of Toni’s princess cake, her competitors’ renditions were, somehow, even more atrocious.

eldritch

More about gloaming

Gloaming, “twilight, dusk,” ultimately comes from Old English glōmung, which occurs once as a translation of Latin crepusculum “dusk, twilight.” Glōmung is a derivative of glōm “twilight, darkness,” from the same root as the verb glōwan “to glow like a coal or fire” (gloaming being the glow of sunrise or sunset). It is tempting to include gloom and its variant glum in this group, but the philological evidence is against it. Gloaming entered English before 1000.

how is gloaming used?

During the workweek, when we are earning the money to pay for all those expensive gardening implements, it’s not possible to do much outside until dusk. Then, with the fireflies, we emerge into the gloaming armed with an arsenal of rakes, pitchforks and spades, like some medieval rabble on its way to battle.

Fortunately, at certain times and places Mercury is more removed from this all-obliterating influence than he is at others, and at such times he may be very distinctly seen, shortly after sunset, twinkling through the gloaming in the west.

gloaming

extramundane

adjective

beyond our world or the material universe.

More about extramundane

Extramundane, “beyond the physical universe,” comes from Late Latin extrāmundānus “beyond, outside the world,” a compound of the preposition and combining form extra, extra– “outside, beyond” and the adjective mundānus “pertaining to the world, the physical universe” and also “inhabiting the world, cosmopolite,” a step beyond urbane, so to speak, and also quite different from the current sense of mundane: “common, ordinary.” Cicero even has Socrates claiming cīvitātem… mundānum “world citizenship.” Mundānus is a derivative of the noun mundus “the heavens, sky, firmament; the universe; the earth, the world, our world,” a loan translation of Greek kósmos. Extramundane entered English in the second half of the 17th century.

how is extramundane used?

One of the subordinate bodies or bureaus or the British Astronomical Association, a company of learned and industrious men who find more pleasure and profit in the investigation of extramundane affairs than in the study of politics or art or other trivial earthly things, is devoted exclusively to the observation of Mars.

I know that there are extramundane occurrences, and I’ve had my share of experiences that can only be explained as ‘supernatural,’ but they have always been the exception.

extramundane